Performance lecture with live video and ritual

Resurrecting the Angelic Works of John Dee

“If we are to suppose a miracle to be something so entirely out of the course of what is called nature, that she must go out of that course to accomplish it, and we see an account given of such a miracle by the person who said he saw it, it raises a question in the mind very easily decided, which is, is it more probable that nature should go out of her course, or that a man should tell a lie?”

Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason, 1794.

Glendower: I can call spirits from the vasty deep.

Hotspur: Why so can I, or so can any man, but will they come when you do call for them?

William Shakespeare, King Henry IV, Part I, III, i, 1597.

This page has extensive stills, previews and research materials from Magickal Realism, which used live integration of video, animation, readings and performance to recreate the life, work and magic of Dr John Dee, the proto-scientist, court wizard and fortune-teller to Queen Elizabeth I. ‘Magickal Realism’ sits somewhere near the centre of a Venn diagram comprising equal parts of:

1. The performance lecture format from my previous Nowhere Plains.

2. The hands-on, lowbrow intimacy of Elizabethan theatre.

3. The Japanese formal rakugo (a long and ridiculous story by a seated storyteller), specifically kaidanbashi (ghost stories that are old-fashioned but nonetheless intended to scare).

4. Newfangled digital VJ action!

The first performance was on Wednesday 24th February 2010 at Colchester Arts Centre, a wonderful former church complete with a graveyard. Then the show toured various English venues, museums and universities later in 2010, and was subsequently updated and restaged in Germany and Spain. The Spanish exhibition version of it eventually had about 44,000 visitors, in addition to its live and webcast audiences. Magickal Realism has been discussed in several books and academic papers about performance art and John Dee, inspired an Icelandic metal band, and it’s been blatantly ripped off by people far more famous than me, without credit, at least twice that I know of… when that happens you really know you’re doing good work (#SARCASM). I have a Magickal Realism album on Vimeo where you can see some of the video mixes and animations I made for the show, although the exact live content changes every time because most of the mixes are done live. You can read about the 2013 incarnation of the show here.

Supported by the National Lottery through Arts Council England, 2009. Additional support by ArtSway’s Associates programme. An early experiment / ritual connected to this project took place at the Art of the Overhead festival in Malmö, Sweden, in May of 2009.

Left:

A posthumous, 17th century (1667?) portrait of Dee as an old man, by an unknown English artist. Dee had been dead for over fifty years by the time this was painted, so it was probably based upon an earlier print. Correction– the book this information came from had it totally wrong.

It was painted from life when Dee was aged 67 and is therefore circa 1594, about 15 years before his death. The painting belonged to Dee’s grandson Rowland and then to Elias Ashmole; it’s now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. John Dee was a major contributor to wizards having long white beards in subsequent popular culture.

The Delta [∆, fourth letter of the Greek alphabet, pronounced “th” as in “this” but usually romanised at “D”] was Dee’s punning symbol for referring to himself. ∆ is used extensively in advanced mathematics, as Dee would have known very well, and of course the triangle has all kinds of magical and symbolic resonances. Also used in genetics notation to stand for a gene deletion.

Things I learned from doing the first performance of ‘Magickal Realism’:

1. No matter how clearly one signals that the narrator is (as all narrators are) unreliable and that there is no such thing as objective truth in history or culture, there will always be a few absolutists determined to believe and determined to have, neatly laid out for them and tied up in a bow, the big answers that nobody on earth has ever been certain of. Just like Edward Kelley you can tell someone directly that you are a liar and instead of being properly wary people are often disarmed and swing to the opposite extreme of total credulity because most of us delude ourselves and tell little lies constantly but who goes around telling everybody that they’re a liar? I think there may have been a few people there who hoped, expected or fantasised that I might actually contact the spirit world for real. Fortunately it’s not as easy as that, especially since I’m not really a wizard. I just have a stick-on beard and moustache that makes me look like one. See the Shakespeare quote at the top of this page.

2. Within moments, participants from the audience fall into a very similar power and interpersonal dynamic with me as is evident in records of the relationship between Dee and Kelley; people in the Kelley role are eager to please an apparently knowledgeable authority figure and yet prone to fleeting rebellions and sulks, but ultimately they provide what they think is wanted of them even though it may be in a manner that nobody could predict, even themselves.

3. Talking in 16th century vocabulary and theatrical idiom is strangely addictive and surprisingly easy. Swearing or exclamations are particularly enjoyable.

4. Working multiple electronic devices and outputs, and managing lots of digital files while talking and performing is difficult. I knew this already, but I still forget it sometimes.

5. Five century old jokes about religious intolerance still offend some people.

John Dee and Edward Kelley

In the 16th century Dee and his partner Edward Kelley (AKA Talbot, a convicted fraudster who had lost his ears while in the stocks for forging money) conducted a series of “Angelic Actions” in which they supposedly invoked spirits and angels. William Godwin’s early 19th century Lives of the Necromancers gives Kelley an unflattering reference:

“Kelly was a notorious profligate, accustomed to the most licentious actions, and under no restraint from morals or principle… Kelly was an impudent adventurer, a man of no principles and of blasted reputation; yet fertile in resources, full of self-confidence, and of no small degree of ingenuity… as interpreter to the spirits, and being the only person who heard and saw any thing, we may presume made them say whatever he pleased.”

Dee, meanwhile, in his youth was regarded as a mechanical prodigy. His machine animals and automata included a giant, animated insect for a stage play. These were considered nearly as uncanny as his associations with sorcery. By the age of 23 he was a star of sorts, lecturing on Classical science and mathematics to large audiences in England and in Europe. In 1583 he had nearly 4000 books and manuscripts, including some going back to the Norman Conquest. For comparison, in 1582 Cambridge University Library held only 451 documents. Dee’s was one of the world’s most remarkable libraries at a time when the majority were illiterate and books were only just starting to be produced in large numbers. It shared the fate of history’s other great libraries; towards the end of Dee’s life it was plundered by erstwhile friends and then ransacked by a superstitious, ignorant mob.

Throughout his life Dee occupied a place between medieval superstition and the incipient scientific age, sometimes tending towards one side or the other but more often partaking equally of both. This was a very risky lifestyle but surprisingly common at the time. Dee was a lifelong confidant of Elizabeth I, and she enjoyed visiting his laboratory at Mortlake. Many aristocratic figures employed astrologers, alchemists or other esoteric professionals. “The Wizard Earl” Percy had a trio of mathematicians, his “three Magi.” Sir Walter Raleigh’s manservant Walter Warner was widely reputed to be a “conjuror”, which is precisely why Raleigh employed him.

It’s also likely that Dee’s notoriety in London and at Court (or direct meetings with the man himself) significantly influenced the characters of Faust in Christopher Marlowe’s eponymous play and the wizard Prospero from Shakespeare’s ‘The Tempest’. And so, despite the neglect of Dee as a real individual, he at least lives on in our cultural memory through Prospero and Faust. It’s been suggested that Subtle in Ben Jonson’s 1610 ‘The Alchemist’ is a satire on Dee and Kelley; Subtle is a blatant charlatan whose cheek is only exceded by the gullibility of his clients.

The Angelic Actions

Full transcripts and descriptions of the Actions— meticulously recorded by Dee— are available and I used them as source material. These and other records of magical practice from the period rarely resemble the spectacular black magic that irreversibly entered public consciousness during the Puritan witch hunts and has stayed there ever since. In fact, the affirmations and planned consequences most closely resemble the endless stream of personal advice on contemporary TV, in magazines and in self-help books. Elizabethan magicians sought fulfilment, wealth, lovers and the meaning of life from demons and angelic spirits, rather than seeking them in Neurolinguistic Programming, dubious and self-appointed experts or fad diets.

The concept for this developed from other works I’ve made for performance and video, dealing with storytelling, historical artefacts and pre-industrial British culture. It will form part of a much larger, long-term project reconnecting contemporary art with traditional British forms and genres, with the aim of taking our own historical culture as seriously as most other nations take theirs, but without any nationalistic or guilty overtones. Specifically I want to illuminate and rediscover some of the important but underappreciated people, events and ideas that have nonetheless shaped our country and the world.

You might wonder why I think a project like this is important, and here’s a roundabout kind of answer: I recently encountered a wonderful statement of intent from the Swedish Ministry of Culture, of all places. Their objectives include “artistic renewal and quality, thus counteracting the negative effects of commercialism; enabling culture to act as a dynamic, challenging and independent force in society; preserving and making use of our cultural heritage… promoting international cultural exchange and meetings between different cultures in the country” [my emphases, original document is here]. I don’t think I can express it any better; this is what art and artists are for. Too many artists spend their whole careers alienated from real culture, recapitulating art world conceits that were exhausted thirty years ago or more, conceits that even back then never meant very much to anyone but a few curators, critics and academics.

Even in its current sadly impoverished and much reduced state, the UK has one of the best, most comprehensive, most generous and most socialistic systems of public support for artists in the world, and I couldn’t have had my career without it. This project would not exist without that system and our farsighted, idealistic ancestors who put it in place because they believed that free and equal access to health, housing, education and ideas were the right of all people. But when was the last time we talked about “preserving and making use of our cultural heritage”, with “preserving” and “making use of” equally valued? Right now it’s particularly important that we find positive and inclusive ways of doing this, otherwise we’re left with a cultural vacuum that racist ignoramuses like the BNP and their apologists are only too happy to fill, propagating their own self-serving, spurious, fictional histories and disingenuously cloaking themselves in the rhetoric of ethnic victimhood. Two previous works by me, Taxonomy and Three Times True, draw attention to the utter and objective fallacy of categories like “race” or “racially pure” and of terms like “indigenous” or “native”.

Celebration of unique, critical voices and traditional culture occur quite uncontroversially in many places I’ve been to as a working artist, including places as distant and culturally disparate as Scandinavia and Japan. Japan officially recognises not only artworks and historical figures but also living people and their practices as irreplaceable national treasures. In Sweden, in Japan, across Europe, Asia, Africa and beyond, governments and ordinary individuals feel strongly that their culture and history is valuable, interesting and relevant; that they are living, personal things worth fighting for. In my home country we’ve lost that notion, allowed it to be taken from us, and allowed it to be hijacked by hatemongering bigots. I’d like to start working positively within that kind of framework again, just as my friends and colleagues in Europe, China and Japan do.

Anyway, putting aside the politics of being an artist in this country during the dying years of Capitalism, I hope that the ’Magickal Realism’ Actions are exciting, compelling and scary combinations of performance, theatre, storytelling and installation. It’s certainly not about nostalgia, but instead about an active and critical engagement with our own history. My Actions will utilise contemporary technology as a delivery method and as the source material for wizardly interpretation: television, radio, wireless equipment, the internet; they will also call upon contemporary, secular heroes and villains. Instead of invoking the Archangels, an Action seeking positive change in the world might call upon Anne Frank*, John Lennon and Winnie the Pooh. Dark forces could threaten in the form of Darth Vader or Richard Nixon. The audience will play an integral, active role in the Actions, which will change according to their individual responses, questions and input.

Existing theological frameworks and faith are mostly irrelevant; these types of Actions often work in spite of an individual’s belief or disbelief. Some people will recognise this philosophy as being borrowed from and/or vaguely in line with contemporary Chaos Magic(k). Before anyone gets too excited it should be noted that although I’m convinced that esotericisms and religions work in the sense that they produce certain effects- some of them positive, and sometimes including physical and measurable effects- and that many people sincerely experience things which can be interpreted as contact with spiritual beings or forces, I don’t believe that the Christian God, any other god, VALIS, Jungian archetypes, machine elves or any other form of disembodied consciousness exists in any objective sense. I think Aleister Crowley’s “by doing certain things, certain things happen” is supportable, but that’s as far as it goes.

This returns us to the lovely bit quoted as the top of this page from Norfolk corset-maker, advocate of common sense, later secessionist and Founding Father of the USA Thomas Paine: “If we are to suppose a miracle to be something so entirely out of the course of what is called nature, that she must go out of that course to accomplish it, and we see an account given of such a miracle by the person who said he saw it, it raises a question in the mind very easily decided, which is, is it more probable that nature should go out of her course, or that a man should tell a lie?”

*NOTE: Anne Frank was also a young servant who worked for the Dee family. She became “meloncholie”: a catch-all contemporary term for anyone mentally ill who didn’t appear to be a dangerous lunatic. On several occasions Dee or other servants prevented her from throwing herself down a deep well on the property. Although she was watched constantly thereafter, one afternoon Anne was able to slip away for a few moments and cut her own throat in the room where Dee and Kelley’s Actions had formerly taken place.

Below: Two parts of the background video mix. The first accompanies a spoken section on the metaphysics and beliefs of Tudor and Elizabethan England. It’s made in the style of a toy or automaton theatre from contemporary woodcuts.

Below: First ten minutes from the live video mix with original animation and video by me, found, out of copyright and archive footage.

The performance is as follows

1. Introduction to the life and work of John Dee and Edward Kelley, with live performance, readings, animated films and video mixes.

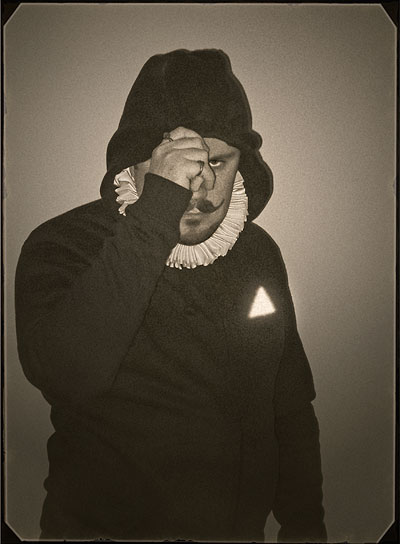

2. Startling horrorscopes by Doctor John Dee and his magical plague mask. The Dee children all contracted bubonic plague during an English outbreak circa 1600. John’s long-suffering but beloved wife Jane was so wise and dedicated in her care for them that they all survived. Unfortunately she herself was infected and died soon afterwards.

The mask used in the performance and films is shown here in a calotype photograph. Made of leather, lacquered crocodile skin and brass goggles. Closely based on real historical examples like the one shown here.

It’s unlikely that Dr. Schnabel was a real person, however, since “schnabel” is simply the German word for “beak”— obviously a reference to the long nose which was filled with perfume or herbs. This was believed to protect against infection by cancelling evil smells and invisible miasmas. Handheld nosegays with the same function were also common. In this period a connection had been made between dirt, decayed or infected matter and disease, but without knowledge of microscopy, internal physiology or epidemiology the only way that most people could imagine being infected without being touched was via the bad smells produced by sickness and filth. The form of these masks still exists in Italy as the Medico della Peste (“Plague Doctor”), one of the five “standard” Venetian Carnevale masks.

3. Discourse and revelations via the Black Mirror and aethyr waves from the mummified head of Dee’s scryer, Edward Kelley. Dee owned an Aztec “smoking” mirror made of obsidian and other priceless oddities from the New World, probably plundered by English privateers from Spanish conquistadors who had in turn plundered them from the original owners. The mirror and some of Dee’s magical paraphernalia can be seen in another part of the British museum.

Dee coined the term “British Empire” in 1577, before the empire itself existed, and he accurately predicted its eventual extent. In 1583 he drew up plans for the colonisation of Atlantis (his name for what would become known as North America). The first stage was Walter Raleigh’s expedition to Virginia, which was named for the “Virgin Queen” Elizabeth. Sadly, Dee’s pious emphasis on “lawful and peaceable means” was mostly ignored.

In the 15th and 16th centuries the Aztec god Tezcatlipoca was known as “The Enemy of Both Sides” and “Lord of the Near and the Nigh’. The former epithet is particularly apt for Kelley; see his espionage connections below. It’s either a bizarre irony or the genius of a born con man that during an Angelic Action, a spirit speaking through Kelley warned Dee that EK was a liar and should never be trusted.

After their relationship had deteriorated to such a degree that Dee preferred to return alone to the England that had effectively exiled him many years before, Kelley slid back into the scams and impostures of his youth. He met his sad and lonely end after being jailed in Eastern Europe for pretending that he could manufacture gold. He tried to escape by climbing out of a window at the top of a tower where he’d been imprisoned but he fell and broke both his legs, among other things. Kelley died in agony and still in captivity shortly afterwards.

In the show, Kelley’s head contains a device that emits prophecies and communications detectable by nearby radio receivers. He wears a replica of an obsidian Tezcatlipoca mask from Mesoamerica, modelled on a real one in the British Museum.

Before he even met Dee, Edward Kelley was a magnet for trouble and a reckless seeker of forbidden knowledge. In addition to his legal convictions for forgery and fraud, he was a self-confessed complusive liar and entangled with espionage. He may even have been initially sent to Dee as a provocateur or spy, at the behest of the first coherent and organised English secret intelligence service. Its master was Sir Francis Walsingham, known as “W”. This is sometimes suggested as the origin of spooks being identified by an initial, as M and Q are in the James Bond books and films; a detail which was in turn cribbed by Ian Fleming from real positions at MI6 in the 1940s and 1950s.

A collective finding and purging of Terrorists with the aid of remote viewing and magic poppets— effigies made on the principle of sympathetic magic, and Tudor forerunners of the now more familiar “Voodoo doll.”

A poppet of Queen Elizabeth found under a tree in London caused widespread and genuine concern. Dee was, ironically, one of the few voices of secular reason who allayed fears for Her Majesty’s life. Years later another Elizabeth poppet was made by Catholic “projectors” (conspirators) with the aim of sickening or killing the queen, and was part of the evidence that informed their death sentences.

Whether innocent or occult, the making or possession of dolls could be a reason or a pretext for torture and execution in the Tudor period, through the later Puritan witch hunts in England and New England and in some parts of Europe well into the 19th century. At the Salem Witch Trials in Massachusetts, some of the women “making poppets and graven images”— i.e. sewing and drawing for their own amusement or that of their children— was deemed a clear signal of witchcraft and evil intent. The arrest of American artist Steve Kurtz in 2004 because of laboratory equipment seen in his home was a 21st century find-and-replace edit of the same old scenario, with “bioterrorism” instead of “projecting” and “petri dishes” instead of “poppets.”

Bruce Schneier published a brief but excellent summary of the ways in which simplistic and paranoid media-friendly narratives are the main influence on so-called “security measures”, which are almost entirely reactive and futile rather than proactive and productive. Any meaningful improvements to collective safety would by their very nature be almost invisible and have little impact on the lives of peaceful and law-abiding people, a situation which in turn would be detrimental to the rhetoric of fearmongering politicians and deprive the media of profitable hysteria and hype.

“The scientist who sits where he is told to sit and looks where he is told to look is the ideal subject for the whiles of the conjuror or the medium, and before him effects can be brought off that would be impossible before an audience of schoolboys.”

William Marriott.

The stage magician and illusionist William Marriott thoroughly debunked the Edwardian craze for seances, Spiritualism and “materialisations” in a series of articles published in 1910 under the title ‘On the Edge of the Unknown’. He was a rationalist who had grown indignant and saddened that so many people took what happened in the seance room at face value, often to the detriment of their finances or sanity, so he set out to demonstrate how easy it is to make it seem that supernatural forces are at work.

In this photograph he is surrounded by “spirit hands”, all in fact produced and controlled by him despite the fact that he appears to be tied to a chair. The “spirit forms” he materialised in his own seances were papier mache glove puppets wrapped in white sheets, but this didn’t prevent seance-goers from swearing they had been visited by spririts. Many of them didn’t even change their minds when he told them bluntly that he was a fake and presented them with the actual puppets he’d used to dupe them. In the seances of “’real” mediums, Marriott sometimes grabbed or chased spirits that always turned out to be fake.

Numerous mediums unmasked as blatant frauds continued to be defended by their own victims. A popular excuse was that they were normally sincere and had only cheated on the occasion when they were caught. Another common attempt to wriggle out, still used today, was that the spirits had fled because they were disturbed or angered by the presence of sceptics or unbelievers, or by science itself.

Dee always maintained that his activities were godly and orthodox; it seems he was sincere in this belief although it would have been wise for him to say so even if he believed differently. In the 16th and 17th centuries several waves of religious dissent and persecution took place in England, mainly afflicting Catholics but also occasionally reaching out for Protestant heretics, schismatics and dissidents, or even some people who thought of themselves as adherents of the relatively new Anglican Protestant church. It had been decisively severed from the church in Rome by Elizabeth’s father, Henry VIII. Following Henry’s somewhat self-serving lead, the English church took particular exception to the supposed ‘idolatry’, greed and usury of Catholics. Further anti-Catholic sentiment was stirred by English colonial rivalries, warfare and a long-standing unfocused antipathy with Catholic France and Spain. The popular media and virtually every church visit were full of warnings against Popery and the evil designs of the Spanish, the French, the Dutch, etc.

The now infamous Guy Fawkes was just one of a fairly large group of desperate Catholic conspirators who felt themselves increasingly cut off from what they regarded as the true church and had therefore planned to create a coup by blowing up the King and the entire English Parliament. Ever since then there’s been a typically English ambiguity with regard to whether the November 5th Bonfire Night is celebrating Fawkes’ failure or the fact that he came so close to succeeding. Halloween and Bonfire Night are a Christian overwriting of the Pagan/Celtic festival of Samhain, with effigies or “Guys” burned instead of live animals or people. Both of these traditions survived relatively unscathed as genuinely vernacular, unique and community-led events until within living memory. Now they have mostly died out, atrophied into perfunctory firework displays or been overwritten in turn by the anaemic, sanitised and commercialised American concept of Halloween.

One of the few exceptions to this national amnesia still takes place in the Southern English town of Lewes every year, and even in the era of political correctness and crippling Health & Safety regulations it gives a rather vivid impression of what a proper Bonfire Night (or a proper burning of actual Catholics or witches) would have been like in the past. The sounds of this night are nearly as extraordinary as the sights, and neither can be adequately captured by images or recordings. I remember standing on the hill where the castle once was, looking down and seeing most of the houses evidently empty because nearly everyone was in the streets, bonfires in a few places, tiny flickers of burning torches and flares threading through the streets everywhere and the sounds of ecstatic screams, hooting, conversation and laughter from all over town for many hours after the official events had ended.

6 thoughts on “Magickal Realism 2009-2010”

Comments are closed.