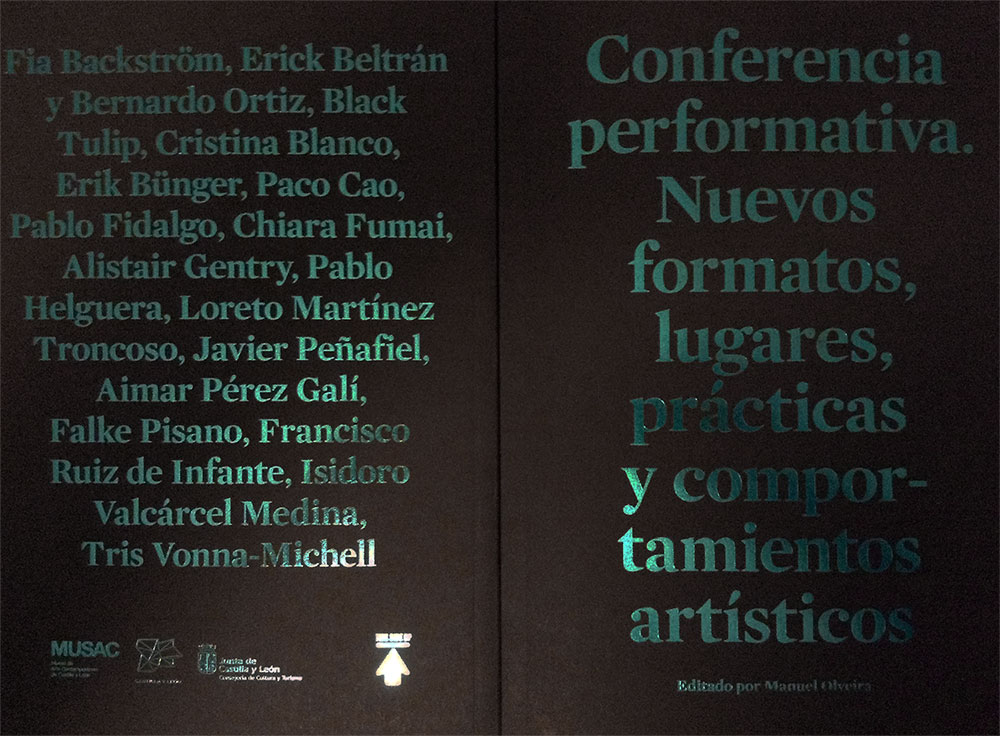

I was interviewed by Manuel Olveira, director of MUSAC (Museum of Contemporary Art in León, Spain) and curator of Conferencia Performativa (Performance Lecture), the exhibition which featured live and recorded versions of my performance lecture Magickal Realism. The interview has now been published in the eponymous book, but in Spanish only so here’s the original English one. See more about Magickal Realism at MUSAC here, or read about the original show here.

Manuel Olveira: Can you introduce briefly the performance-lecture?

Alistair Gentry :Magickal Realism is a performance lecture with video and animation. It’s inspired by the 16th century wizard and proto-scientist John Dee. It’s about 60-90 minutes long and it includes readings from his own diaries, and my own telling of his life, his death, his magic, his relationship with a con man called Edward Kelley, and his relationship with invisible beings that he called Angelic Spirits.

MO: You performed this lecture for the first time in 2009-10 and it recreate the life and work of Dr John Dee, the proto-scientist, court magician and fortune-teller to Queen Elizabeth I. Quoting your blog: “Throughout his life Dee occupied a place between medieval superstition and the incipient scientific age, sometimes tending towards one side or the other but more often partaking equally of both. This was a very risky lifestyle but surprisingly common at the time. Dee was a lifelong confidant of Elizabeth I, and she enjoyed visiting his laboratory at Mortlake. Many aristocratic figures employed astrologers, alchemists or other esoteric professionals. “The Wizard Earl” Percy had a trio of mathematicians, his “three Magi.” Sir Walter Raleigh’s manservant Walter Warner was widely reputed to be a “conjuror”, which is precisely why Raleigh employed him”. Why were you interested in him for the lecture at Colchester Arts Centre? Full transcripts and descriptions of the Angelic Actions— meticulously recorded by Dee— are available and you used them as source material. Could you tell us more about the Actions?

AG: The Actions were his seances or spirit-contact sessions that he conducted (mostly) with his partner Edward Kelley. They used various paraphernalia that I have also sometimes used in my performances: drawings of sigils and magic circles, candles, wax pentacles, mirrors, polished stones. Some of these items miraculously survived into the present, including a black obsidian mirror that came originally from Central America. All his stuff is now in the British Museum. The Actions also involved mysterious mathematical calculations and tables, and the spirits (or rather, Kelley) communicated in a unique language, “Enochian”, supposedly the language of angels. In performances of Magickal Realism– and in a few of the videos– examples of Dee’s mathematics and the Enochian script can be seen occasionally, although I don’t really go into them in detail because they’re very esoteric and complicated. I have some understanding of them but they’re probably not very interesting to a general audience. That’s another place where the “performance” part of “performance lecture” is important. The lecture is not only, or not primarily, intended to convey factual information in the way that a real lecturer or teacher would if the listeners were taking an exam or studying a course in the subject. Entertainment and aesthetics are also important.

As a live performance predecessor of Magickal Realism, I re-enacted some of the actions, but in the style of university lecture. On one occasion I was followed by a real lecturer. The way he looked and the way he talked about contemporary science were so close to what I’d just done in the context of talking about magic… it was a bit embarrassing. It probably looked like I’d deliberately satirised him personally, although I didn’t mean to because I never met him before.

MO: You started in the theatre and that can be seen in the way you perform the lecture. How did you get in touch with Lecture performance?

AG: I started out in devised theatre (i.e. improvised and without a script), then I worked as a playwright, but very quickly I found writing for theatre and writing radio plays restrictive and formulaic. So after that I started making sound and installation works for galleries. They still always had some element of narrative, but it took me about ten years to find a viable way of doing what I’d always really wanted to do, which was combine some elements of traditional theatre and theatre craft with some of the more exciting aspects of gallery-based performance art, video and digital art.

MO: What sort of things appealed to you most?

AG: Mainly being able to do everything myself, using my background in theatre, and making a direct, human connection with a live audience, although I’m sometimes a bit too ambitious and try to do too much and convey too much information in one show. I had the opportunity to work on a few more mainstream film or dramatic projects, and I found that being a proper film director was mostly quite tiresome because you have to also manage the crew, the set, the technology, the timetable, placating producers and funders, just everything you can imagine, in addition to directing the film. I didn’t really like it. It seemed like the wrong mixture of 95% boring work and 5% creativity.

I also like to play around with the fact that somebody in a position of power and authority (such as a lecturer or actor) can do almost anything they like if the audience trusts them. I sometimes lead them to trust my word and then deliberately undermine my own authority. I don’t think there’s any such thing as a totally objective truth, so pretending to be different characters for different works is a way of reminding people that the things I say often are true, but nobody should take it for granted that they really are true. They should use it as an opportunity to think for themselves, not have me do it all for them.

MO: Could you tell us something more about Dee topics on your work?

AG: In this work I was particularly interested in the very, very close parallels between the politics of Dee’s time (late 16th-early 17th century) and the present. Back then Protestant Christianity and Catholicism were fundamentally opposed, and many people on both sides killed or were killed because of it. England and Spain were particular enemies. There was paranoia about Catholic plotters and terrorists in England and Scotland, and there were even a few real terrorists who plotted to start civil wars, international wars, or install their own chosen rulers by force. Guy Fawkes and his fellow Catholics’ attempt to blow up the Houses of Parliament in London with gunpowder was one very real plot that almost succeeded. The rulers of England also took every opportunity to whip up hysteria and hatred for propaganda purposes, to serve their own selfish interests: wealth and power. There were spies and informers everywhere. Torture was carried out against the innocent and the guilty alike. With all this said, I think the parallels are very clear. Just substitute Muslims for Catholics, and almost everything is the same. A few real zealots who want to commit mass murder, alongside a mostly unrealistic popular narrative that certain groups of people, usually foreigners, are not to be trusted. Real or imagined plots used as a pretext for warfare, colonialism and mass murder.

There’s also a very clear parallel between the way Dee came to a very sad and lonely end, and the way that other great and wise people have been used and then discarded by the ruling powers throughout history, and in the present. Dee’s plans for the colonies in the New World warned that the people who already lived there were fellow human beings and not just savages; that they should be treated in the spirit of Christ, as brothers and sisters. He was ignored, of course. Colonialism was really about natural resources and profit, just as the modern developed world’s concern for stability in the Middle East and Africa is mainly about oil and mineral resources. Edward Snowden is an almost Dee-like figure, an expert who turned against the immorality of what his masters were doing and now has all kinds of spooks and zealots calling for his head.

Finally, Dee actually did performance lectures as a young man, very similar to Magickal Realism. He made plays with mechanical and optical effects, and he toured Europe to sold-out theatres with a lecture on the latest developments in mathematics and cartography. As a young man he was a genuine celebrity. He had fans.

MO: Why are you interested in re-reading aspects of the past and specially the figure of Dee?

AG: My other live or video work is about unappreciated historical figures, the survival into modern times of very old stories and strange ancient beliefs, or the way that history never really goes away. You could say that all my work is about those things that are quite important in some way, but still hardly anybody knows about them.

MO: Superstition never dies…

AG: The esoteric, in the widest sense of the word. It’s very common for modern people to mock their ancestors for their credulity and barbarism, but people still believe irrational things today. Only the content has changed, not the underlying lack of logic or the irrational things that people do because of faulty logic and prejudice. I think history always has lessons we can learn in the present, though, if we can get past the superficial differences in how people used to live.

I’m also delighted by the patterns you find in history, where certain specific relationships, scenarios, and chains of events seem to repeat themselves exactly, but in different contexts. Even certain people seem to repeat in some weird way. One of John Dee’s housemaids was a girl called Anne Frank, who wrote a secret diary and died very young under horrible circumstances. It’s probably just apophenia, the human tendency to see patterns in everything, but that in itself is an interesting thing to talk about.

MO: As I can see you have clear influences based on theatre, history and unappreciated historical figures. What about art? Have you been influenced by other artists? Do you see yourself close to other artists? What do you like best about their work?

AG: I don’t fit very well in the orthodox art world, because I’m more interested in ideas than in exploring one way of working or one medium forever, which is how you usually build a career and become well-known as an artist. There are lots of artists I like, historically and in the present, but I wouldn’t say I’m very influenced by any of them in a direct way. I like some of Susan Hiller’s work a lot. She seems to have a lot of interests in common with me– ethnography, memorialisation, the paranormal. The mysticism and hermeticism of Yves Klein (and the way it manifested in his work) interests me. I like Chris Marker’s work, his very rambling, impressionistic documentaries and his installations. I like a lot of the work that some artists have done recently in collaboration with scientists and researchers. I’ve done some of that kind of work myself. In this exhibition I particularly liked Chiara Fumai and Paco Cao’s work. I respond to any kind of art work that you really need to be with physically and/or spend time with in order to really understand it. I hate art works that are just conceits or high concepts… “wouldn’t it be funny/arty/weird/disturbing if…” There’s a lot of that about. It seems to be very much approved of at most art schools. Those kinds of art works may as well just be written on a piece of card or told to the artist’s friends. There’s no point making the art work because you can know everything there is to know about it in a few sentences. You don’t need to see it or experience it. I know a lot of artists make whole careers out of just reacting to the art world or pandering to current critical consensus, but for me it’s quite boring to only react to the work of other artists in your own art. I’m much more directly influenced by popular culture– films, video games, the internet– and by reading science books or research papers, novels and all kinds of books about everything except for art. Also by theatre, aesthetics and storytelling from outside the Western tradition, Chinese and Japanese especially. There still don’t seem to be many artists working in the way that I do. I really identify with artists like Chris Marker or Vincent Van Gogh, who just did whatever they wanted, were 100% focused on their work, and only explored what they thought was worthwhile, even though most people didn’t get it at the time. I’m not going to cut my ear off, though.

MO: Would you say that you’re trying to postulate alternative values concerning with History?

AG: I don’t know if it’s very alternative or subversive any more, but I definitely think there’s still a tendency for most people to think that history is a fixed, objective and factual thing. I just don’t see it that way, so the way I talk about history isn’t fixed, objective or necessarily factual either. I guess that’s why you’d call it a performance lecture and not just a lecture. History is a product of the historian, it’s a narrative and it’s ideological. It’s not an objective and separate entity. Events that happened can’t be changed, but history can change. It can be revised or erased. Even our own memories of things that happened to us directly can be changed, expanded, revised, erased or entirely false from the start… so it doesn’t make sense to me that anybody would think history was fixed or permanent either.

MO: What do you think makes Dee particularly important today?

AG: Dee is a very important historical figure in English and world history, but even by the end of his lifetime he was almost totally forgotten. In the last few decades there’s been more recognition that his influence was huge, and hopefully I’ve played a small part in that revival of his reputation. He invented the term “British Empire” before there was one, and he advised Queen Elizabeth I about where the English should send their exploratory and colonising ships… and he decided this equally by consulting with spirits and by his almost unequaled knowledge of cartography and mathematics. He had one foot in the medieval world of magic, the other foot in the Renaissance and science. He inadvertently founded a new Western esoteric tradition that leads through to all kinds of people including the Satanist Anton Le Vey, “The most evil man in the world” Aleister Crowley, and the whole New Age movement. He directly influenced popular culture and literature, because his long beard and robes were the prototype for the image and aesthetic of the wizard as a frail but very powerful old man, from Prospero in Shakespeare’s ‘The Tempest’ to Gandalf in ‘Lord of the Rings’. Hardly anybody knows this, and as I said before, one of the main concerns in my work is opening up neglected areas of knowledge and history to a wider audience.

MO: You are re-reading different aspects related to Dee and his time. So, you are using information in a personal way of approaching it. The concept of information and evidence has allowed any number of seemingly disparate phenomena—from genetic material to the temperature inside one’s house, the content of a book, the sound transmitted over a phone line, and more—to be imagined as comparable in some way…and also then, analyzable. Could you explain how you conceive and use the information?

AG: To a large degree it’s just how my mind works. I have a good memory, I know something about most subjects, and quite a lot about certain subjects, but my knowledge isn’t obtained or stored methodically. So all information to me is already in some ways comparable, wherever it comes from. Learning more, and learning disparate things, literally grows new connections in the brain. So the more you connect knowledge together and seek new knowledge, the more new connections you see. Researching my work is exactly like this, too. Unlike an academic or a journalist, I don’t have any particular responsibility to keep fact and fiction apart, or footnote everything, or list all of my sources, or offer proof and evidence. So I can just leap from one thing to another.

Having a mind like this also makes it very clear to me that information or evidence can sometimes be used just as easily to “prove” untrue things, or to create alternative, false, fictional versions of reality that are– at least temporarily– convincing. Some of the props and costume items I use in my shows are real, but others are forgeries that I’ve made and aged to look real. Sometimes I don’t even use them directly in the work, they just sit there, but you could hold them or pick them up and never know they were fake. It’s very common in theatre and film, which is where I got that practice from, but I don’t think there are many performance artists who do it.

I think it’s also a side effect of growing up alongside digital technology. When I was doing sound installations, I would often work with the sounds by looking at the waveforms instead of listening to them. Ultimately it’s all just numbers, which can be expressed in various ways. This reminds me of Dee and his Enochian number tables and symbols again.

In video editing, if you work with performances or dialogue, you can be taught or you can learn all the cheats you need to make cuts and alterations effectively invisible. It’s sometimes called “suture”, alluding to the way audiences can be “sewn in” to the work and temporarily forget that it isn’t real. If you’re an artist, a writer or a film maker it’s hard not to look at everything and everyone in the world as material, and when somebody achieves a particular effect you’re always thinking about how they did it instead of just being able to enjoy like a normal person. I think most people are sutured into the world, too. They can’t see the cuts or the transitions holding everything together.